This article here (link) is one of the best philosophy posts I’ve ever read on substack. Go read it. Now. Read it especially if you are interested in things like consciousness, Kant, and substack posts that don’t suck. I’ll sit here and re-read this Kant comic while I wait for you.

(Did you know that you can make Kant jokes without resorting to contractions? You can!)

Welcome back! Since you’ve read that substack post, you’ll likely agree with me that the author,

, does a great job of attempting to use Kantian resources to build a defense of qualia and phenomenal consciousness against attacks from the growing number of self-styled “qualia quietists,” who, some say, are even worse than illusionists. Illusionists famously think that phenomenal realists are wrong. Qualia quietists hold that phenomenal realists aren’t even wrong, and that illusionists aren’t even wrong either. The only way a qualia quietist is going to concede to anyone that anyone could be either right, or wrong, about whether anyone has experiences with qualia, or phenomenal properties, is if there is something coherent, informative, and non-circular that can be said about what any of the above means. A qualia quietist refuses to either agree or disagree that people are under the illusion that glumpadumpojumbazabooza. Huh? What?Anyway, Guy does an excellent and charitable job portraying qualia quietism. They also do a terrific job briefly spelling out key parts of the past few hundred years of the history of “phenomenal consciousness” from Descartes and Locke in the old-timey times, back when “consciousness” was first entering English, through Kant, who famously made a big deal about distinguishing “phenomenal” and “noumenal”, and up through to Thomas “What-it’s-like subjectivity” Nagel and Ned “phenomenal consciousness” Block in the 20th century.

The gist of Guy’s strategy for defending phenomenal consciousness against quietism is succinctly put like this:

“I suggest that there is a rough mapping (perhaps even an equivalence) between Kantian expressions like “the way this object appears to me” to the Nagelian “what it is like for me to perceive this object”. It's not about sprinkling some magic fairy dust onto an ordinary experience, it's about distinguishing the way things appear to me from the way things appear to you, and distinguishing appearances in general from however things are aside from appearances.”

I think, ultimately, Guy fails to pull this off. While I think it’s fair and accurate to map Nagel onto Kant like this, there’s no way to do so without getting magic fairy dust all over your clothes. Or so I will soon argue. Guy fails for interesting reasons, though, so it will take some time to develop my case here. I don’t think Guy makes dumb mistakes. They are smart mistakes, but mistakes nonetheless. And in some if not all instances, they are old and widely held mistakes, mistakes we can blame on the mighty dead, and so aren’t really Guy’s mistakes. But, says I, they’re still mistakes. These mistakes end up preventing the construction, from Kantian materials, of an innocent and defensible notion of phenomenally/qualitativeness/what-it’s-like-ness/feelyness.

Phenomenal appearances and doxastic appearances

What if we could just identify phenomenal consciousness with appearances? If that could be accomplished, that would be exceedingly good news for anyone who wanted to keep on saying “qualia exist,” since it is exceedingly difficult to deny that appearances exist in some sense or other. It’s both common and useful to distinguish how things seem to someone and how things really are. At a fairly early age most humans can even grasp the three-way distinction between how things seem to oneself, how things seem to someone else, and how things really are. Such a skill remains useful up to adulthood, and beyond.

Here’s a snapshot of adult usage. Suppose Smith and Jones are both being administered a field sobriety test by a state trooper. It seems to Smith that the trooper is holding up 4 fingers, and to Jones, only 2. They both comply with the trooper who announces that he was really holding up 3 fingers and now he’s going to drive them to the station where they can sober up in a jail cell. Smith and Jones aren’t too drunk to appreciate that how things seemed to them differed both from each other and from how things really are. All of this is innocent, anodyne, and nothing for qualia quietists to get in a snit about. So, if someone wanted to use “qualia” or “phenomenal consciousness” or any of the contested terms to refer to the bare minimum we need to make sense of Smith, Jones, and what Smith and Jones made sense of, then no snits need be gotten into. But—and it’s a big “but” (and I cannot lie)—it’s highly unlikely that Kantians, their Lockean precursors, or their Nagelian and Blockean descendants had anything so thin and unobjectionable in mind.

Many philosophers in analytic philosophy follow Roderick Chisholm (1957, Perceiving) in distinguishing between two alleged senses of “appears” and “seems” attributions—a phenomenal sense and a doxastic sense. For people who like this distinction, they hold there to be a fairly clear difference between it seeming like there’s a red apple on the table because and while one is having a visual experience of the red apple being red (phenomenal seeming) and it seeming like today’s Friday and not Saturday (doxastic seeming). It suffices for having a doxastic appearance that such-and-such is the case that one thinks, or judges, or believes that such-and-such is the case. Phenomenal seemings, in contrast, require phenomenal states, states with phenomenal properties.

Roderick Chisholm (1916-1999)

Some allege that phenomenal seemings and doxastic seemings are most clearly separable when we consider cases of recalcitrant illusions, like when the Müller-Lyer illusion continues to seem like a presentation of unequal line lengths despite one’s believing that the lines are actually the same length. In such cases, say followers of Chisholm, the Müller-Lyer lengths phenomenally appear unequal even though they don’t doxastically appear unequal.

I bring all of this up to suggest that if anyone is going to find plausible the suggested identity of phenomenal consciousness and appearances, it’s going to be in the Chisholmian “phenomenal” sense of appearance, not in the doxastic sense. For further evidence that lovers of phenomenal consciousness are unlikely to band together behind the suggestion that doxastic appearances are to be identified with phenomenal consciousness, take a glance at the current state of the discourse over so-called cognitive phenomenology, an ongoing debate in the philosophy of mind about whether there’s something it’s like in the Nagelian sense that attaches to thinking or believing e.g. that 2+2=4 (as opposed to attaching to some accompanying sensory or motor imagery of visualizing “2+2=4” written on a chalkboard or silently mouthing the English words “two plus two equals four”). If you’re not already familiar with debates about cognitive phenomenology, check out this nice IEP article. https://iep.utm.edu/cognitive-phenomenology/

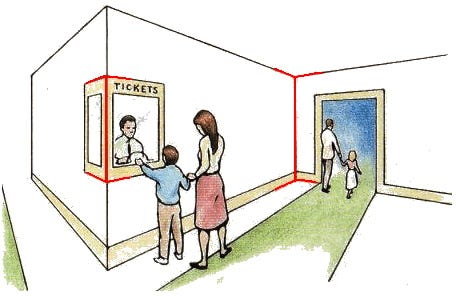

The Müller-Lyer Illusion. The rightmost vertical red line seems longer than the other one, but do you believe that it’s longer? Really? LOL. What a rube.

I bring up this Chisholmian distinction between alleged kinds of appearances not because I think it’s a good distinction, but instead to articulate a problem for Guy’s proposal to wield Kantian appearances to both break out of the phenomenal term circle (the tight circle of synonymous technical terms “phenomenal character,” “qualia,” etc) and to put qualiophila on unquestionable footing.

Let’s first take the challenge posed by the phenomenal term circle. The challenge is to spell out “phenomenal consciousness,” a technical phrase, in non-technical terms. “Seems” and “appears” are both nontechnical, so that seems like a promising way out of the circle. However, if “seems” and “appears” are being used as code for specifically “phenomenal” seemings a la Chisholm, then we haven’t escaped the circle’s gravity at all. We are articulating phenomenal consciousness in terms of phenomenal appearances and thus shedding approximately zero light on “phenomenal”.

Guy suggests that Kantian phenomena can escape the phenomenal term circle in part because “phenomena” is defined contrastively against “noumena,” but this is of no help at all. “Noumena” is defined entirely negatively as what is outside of or independent of phenomenal appearances, and defining A as not B doesn’t help if we don’t already have some independent grasp of what B was supposed to be. What are zorbs? Well, I can tell you one thing about zorbs: they aren’t blorbs! Gee, thanks. Kantian phenomena aren’t an antidote to 20th century circularities endemic to “phenomenal consciousness”, they are major component of the etiology.

The circularity is coming from inside of the house!

The second problem is that it’s the doxastic sense of appearing that has any chance of fortifying phenomenal realism as something even remotely indubitable. The point here is one familiar from discussions of Descartes’ cogito. Doubting is doxastic. So, even if one doubts that things are as they appear, one way that things still are is that there is some doubting going on, and that episode of doubting, being a kind of thinking, is a doxastic appearing. That there is doxastic appearing is a state of affairs beyond Cartesian doubt. But this Cartesian point does absolutely no work at all in securing so-called phenomenal appearances against skeptical doubts.

Doxastic appearances are also what’s doing all the heavy lifting in the popular objection against illusionism that says that there being an illusion requires there being someone to whom it appears falsely that such-and-such is the case. Doxastic appearance is doing all the work here because doxastic appearances are the ones straightforwardly involved in having the propositional semantic content that such-and-such is the case. Whether so-called phenomenal appearances are similarly propositional is a topic of intense and ongoing debate. Setting aside the problem of non-circularly pinning down what “phenomenal” is supposed to mean, we have the further problem of why would the so-called phenomenal appearance of redness be required for anyone to be wrong about anything?

To attempt to answer that question on behalf of Guy, and also to make a graceless segue into a separate problem I have with his argument, maybe so-called phenomenal appearances have a special role to play, not in constituting the truth evaluable states, but as justifying such states considered as potential states of knowing. I struggle to make sense of the following passage from Guy, but my hunch is that it is both key and making a point about justification that I think will ultimately be problematic:

“In order for illusionism to even get off the ground, there has to be an illusion. That is, there must be something that seems some way from someone’s perspective, even if incorrectly. But doesn’t an illusion, by its very nature, require something internalist—a representation that you have cognitive access to without a neuroscientist telling you what your brain is doing? To count as an illusion, the system must be misled in a way that is accessible from the subject’s own cognitive point of view. But if mental and perceptual content is fully external, there is no internal point of view from which an illusion can be recognized as such. […] A purely externalist being may well have false beliefs, but false beliefs are not illusions.”

What’s going on here? One thing that seems to be going on is that Guy is arguing against the adequacy of doxastic appearances for fleshing out an anccount of illusion. I agree that false beliefs are not automatically illusions (and have argued such in my 2016 paper). But what, according to Guy, are the further requirements for illusions properly so-called? Here I think is where I strongly depart from Guy, for Guy is loading a lot of questionable metaphysics and epistemology into the allegedly unobjectionable notion of “appearances.”

The picture Guy sketches in that material I just quoted seems like he’s suggesting we need some phenomenal properties made available to the inner-eye, and once made available to the introspecting person, those properties would thereby be available to that person to cite in requests for justification.

Maybe I’m WAY off base for attributing this to Guy, but here’s my best guess as to what’s going on here. Consider, first, as a warm-up exercise, a case in which Smith is able to distinguish two balls as being different. Smith judges that they are indeed two different balls. Suppose further we press Smith to justify his claim that the balls are different. How, Smith, do you know they’re different? Smith might say that they are different with respect to their color—one ball is red, the other is blue, and he’s in the same well-lighted room as the balls, where he can be counted on to see such differences in ball color. Contrast this case with Jones, who forms beliefs which happen to be true, but when pressed for why he holds the beliefs, Jones just says stuff like “I have no idea” and “I just believe that.” Many such cases like Jones’s have been discussed in the literature (see especially Keith Lehrer’s 2000 discussion of Mr. Truetemp.) In one such thought experiment, imagine that Jones just forms true beliefs about Chicago, even though he’s thousands of miles away and has neither perceptual contact with nor testimony from reliable witnesses on the ground in the Windy City. Perhaps magically or via ESP, Jones just has spontaneously arising true beliefs about stuff happening in Chicago. In standard externalist accounts of justification, Jones’s Chicago beliefs might count as justified on the basis of this magical process being a reliable one for producing true belief. But Jones can give no account of why he holds that it is currently 89 degrees Fahrenheit in Chicago and partly overcast. It just seems that way to him—in the doxastic sense of “seems”.

Let’s go back to Smith now. Smith believes correctly that the balls are distinct in terms of color. Further, when we press him for how he knows that, he can cite that he sees that one is red and the other blue and that red and blue are two different colors. It looks, then, that Smith is able to give an account, a justification in the internalist sense of justification, for his judgment that the balls are different. He can cite something else besides the balls being different, he can cite their different colors and that he can see colors. So far, so good. Nothing problematic so far. But we’re close to running into trouble and we just need to go a little bit more internal, so to speak, inside of Smith.

A Fantastic Voyage

Suppose that, instead of asking Smith how he knows the balls are different, we ask him instead about the answer he gave to our earlier question. “Smith, you say you know the balls are different because you can see one is red and the other is blue. But how do you know THAT? How do you know you see one as red and the other as blue?” What’s Smith going to say? If he says: “I can introspect with my mind’s eye that I’m having distinctly visual qualia, so that is how I know that I’m seeing, not hearing or smelling balls, and I can introspect that I’m having the distinct visual qualia of phenomenal redness and phenomenal blueness,” then he’s throwing us back into the phenomenal term circle. We’re back in the circle since he’s saying “phenomenal” and “qualia.” Bad Smith! Bad!!

But that’s a problem I already commented on above. I want to focus on another problem, and it’s this: We can keep up our questioning, and at some point Smith is going to say something very similar to what Jones says about Jones’s Chicago beliefs—“I don’t know how I know, I just know;” or “I don’t know why I believe that, I just do.” So, if we asked Smith how he knows that his red quale and his blue quale are different quale, is he going to cite another inner-eye, one that’s inside of his first inner-eye? A homunculus inside the homunculus?

A miniaturized submarine inside of Smith locates Smith’s blue and red qualia.

In Pixar’s Inside Out movies, the main character feels angry because her anger homunculus gets angry, and toward the end of the first movie we see that the anger homunculus contains his own set of homunculi. The film isn’t infinitely long, so we don’t get to see the implied infinite series of homunculi-within-homunculi.

(I tried to explain this point about Inside Out to my Philosophy 101 students once and their response was “Professor, are you ever able to just enjoy a movie?” No. I am not.)

Anyway, Smith is on his way to a similar infinite regress and he’s going to drag Guy down with him. The solution, of course, is to abandon internalism, and allow that there are some doxastic appearances that are like the Chicago case: I don’t know why I believe that, I just do. There’s no justificatory problem that phenomenal appearances solve in any way that isn’t better than just ignoring the alleged problem before the regress ever starts. Doxastic appearances are appearances enough. I don’t see any way around the fact that there are always going to be some beliefs or other that we have without being able to give a bullshit-free account of why we have them. I also don’t see that this is any kind of problem, not even a problem for distinguishing illusions from mere false beliefs (see my account of cognitive illusions in Mandik 2016, if you care).

The Unnoticed Vacuity of Idealism

I’m not convinced by any of the Kantian stuff so far reviewed. I feel just as motivated as ever to keep on denying that there’s any informative, noncircular account on offer of either phenomenal consciousness or non-doxastic appearances. But there’s an arguably distinct argument that Guy makes in defense of Kantian phenomena that I will briefly remark upon. Echoing many idealists, Guy remarks that we cannot deny Kantian phenomenal properties because “it's incoherent to say that you can experience the world as it is completely independent of your experience.” (Compare Berkeley’s “you cannot conceive a tree unconceived” so-called master argument for subjective idealism and Schopenhauer’s “Everything that exists for knowledge, and hence the whole of the world, is only object in relation to a subject, and therefore only with reference to the subject...".)

The alleged incoherence “you can experience the world as it is completely independent of your experience “ is significantly ambiguous. On one way of disambiguating this, what’s alleged to be incoherent is something expressing the negation of a tautology, a denial of an utterly undeniable logical truth who’s core logical form is “P -> ~~P,” a form shared by such eternal truths as “if you’re swimming then it’s not the case that you’re not swimming” and “you cannot chop down a tree without chopping down a tree.” Saying such things wouldn’t convey any information to anyone who didn’t already know how conditionals and double-negation work in English. But we wouldn’t be conveying anything about consciousness, or the world, or knowledge, or chopping trees, or swimming. So this isn’t any sort of defense of “phenomenal consciousness”. It’s just a defense of basic logic.

There’s another disambiguation worth considering, one that avoids vacuity but sacrifices indubitably. On this disambiguation, the core logic of the allegedly indubitable claim is a modal claim whose core form is “If P then necessarily P”. The instances of this form having to do with experience or representation would be something like “nothing you experience could have existed unexperienced” or “If something is represented then what’s represented could not have ever existed unrepresented.” Anyone struggling to see how these are highly dubitable non-tautologies might possibly having difficulty avoiding the modal fallacy of confusing “Necessarily, if P then P” with “If P then, necessarily P.” But maybe the following examples will be helpful to anyone having such difficulties. Consider these distinct sentences, 1 and 2:

1. Necessarily, if Linda is wearing sunglasses then Linda is wearing sunglasses.

2. If Linda is wearing sunglasses then Linda is necessarily wearing sunglasses.

That first Linda sentence is not only true, it’s a trivially true, a logical truth. The second Linda sentence is false. Yes, Linda does often wear sunglasses, but she doesn’t have to wear them, she hasn’t always worn them, and she’s not fated to continue wearing them. The second sentence is saying something nontrivial but false. It’s false because people and sunglasses just don’t work that way.

Could we get something with the form of 2 to be true? Like, maybe, change the stuff about sunglasses to something else? Plausibly we can. For instance, there’s this sentence which swaps out sunglasses for blood:

3. If Linda is warm-blooded, then Linda is necessarily warm-blooded.

It’s debatable whether there are essential properties, but it’s not absolute crazy-talk to advocate essentialism. Plausibly, if a creature has the property of being warm-blooded, that’s one of its essential properties. My dog Zelda is a mammal, and all mammals are warm-blooded. If any creature wasn’t warm-blooded, it wouldn’t be a mammal, and wouldn’t be a dog, and wouldn’t be my dog Zelda. I haven’t met Linda, but if she’s warm-blooded, she’s probably a mammal or a bird or some other creature who is warm-blooded by nature.

Can a Kantian make a similar move here, and argue that it’s the nature of reality itself that it is represented? Can the Kantian make the case that being the object of a phenomenal representation is more like being warm-blooded than like wearing sunglasses? And can they do so without committing any modal fallacies? Maybe, but that’s not the sort of thing that anyone’s likely to fit into a short little sentence. That’s the sort of thing that Kant needed two editions of the Critique of Pure Reason to attempt, and the reviews have been mixed, to put it mildly.

All that said, I continue to think that “phenomenal consciousness” has little to recommend it, and that access consciousness is all anyone needs to enjoy their lives, solve the problems of the world, and make progress in the science and philosophy of consciousness. Keep on believing stuff, everybody! Thanks for reading this far, and if you are

, thank you for writing your excellent post. I thoroughly enjoyed reading it and thinking about it and I hope that my long weird failure to agree with it is nonetheless interesting to you. Cheers!

Nice article. I do have some concerns with your treatment of the blue ball-red ball case. Let me try to sketch the issue I have in mind.

Imagine someone overwhelmed with pleasure, so fully immersed that much of their cognitive machinery shuts down. They are not forming beliefs like “I am having a great time,” not reflecting, and not entertaining any abstract propositions. There is no introspection, no metacognitive access, just the experience itself.

Then, suddenly, everything flips. The person is overtaken by intense pain. A mental switch gets flipped. The pain dominates in the same way, without belief, without conceptual grasp. The person still cannot entertain propositions. So in both cases, there is no doxastic seeming.

What I want to claim is this: the person knows that something changed, not because they believed “something changed,” but simply by undergoing the shift. The noticing itself is, I think, a kind of knowledge. Unless we assume from the start that knowledge must involve propositions, I see no reason not to count this.

As for justification, this kind of phenomenal recognition, this awareness of difference, draws on a basic perceptual and experiential capacity. It involves immediate recognition of change, even when the intensity of the experience rules out conceptualization or the formation of propositions. It seems like a good candidate for a foundational belief, even if we are not aiming to build epistemology on foundations. The justification here is direct, not inferential, and not the result of any error-prone process. That does not mean we can build a complete theory of knowledge from this kind of case, and I am not claiming we should. But it does seem to be a genuine instance where justification arises from experience alone, without mediation, and in a way that rightly counts as foundational.

One might object that recognizing contrast between pleasure and pain requires memory, that the subject must recall the previous state in order to register a change. But I think that is not necessary. What matters is that the specious present, the briefly extended now of perceptual consciousness, can contain both affective states. The transition, embedded in that lived moment, already carries enough temporal structure to register the contrast. So the awareness of change does not rely on memory, but on the structure of experience itself. The shift is directly given, not retrieved.

If someone says we can have knowledge of a mind-independent reality, it's not trivial to say, "No, you Kant".